I’m leaving to head to St. Pete Pride this weekend, and it’s got me thinking about the state of Queer characters and storytelling today. I wrote last week about Queer as Folk, and I don’t want to trivialize that show’s importance, but I think the current state of queer storytelling truly shows that QAF is a show of the past and it wasn’t capable of, or perhaps the audience wasn’t ready for it to do the sort of things shows today are doing. I think we’ve officially left behind the time when queer shows and characters were primarily defined by their sexuality. Some part of that can be seen in the titling of shows. We’ve gone from shows like Queer as Folk and The L Word which reference their queer identities in the title, to shows like Looking and Faking It. But it’s about more than just what the shows are called.

I’m leaving to head to St. Pete Pride this weekend, and it’s got me thinking about the state of Queer characters and storytelling today. I wrote last week about Queer as Folk, and I don’t want to trivialize that show’s importance, but I think the current state of queer storytelling truly shows that QAF is a show of the past and it wasn’t capable of, or perhaps the audience wasn’t ready for it to do the sort of things shows today are doing. I think we’ve officially left behind the time when queer shows and characters were primarily defined by their sexuality. Some part of that can be seen in the titling of shows. We’ve gone from shows like Queer as Folk and The L Word which reference their queer identities in the title, to shows like Looking and Faking It. But it’s about more than just what the shows are called. For starters, I think issues of queer visibility have gone through the roof. We’ve reached a point where shows are almost required to feature queer characters in some capacity. And more importantly, these queer characters get to be important to the overall story of the series, while also being more than just defined by their sexuality. There’s Nolan Ross over on Revenge (who beyond being generally fabulous also gets to be one of the few, if not the only, honest representations of bisexuality on TV), Cyrus Beene on Scandal is allowed to be gay and a horrible person too, and everyone’s favorite Sapphic scientist Cosima Niehaus over on Orphan Black (more on this in a minute).

So we no longer have to look to exclusively queer shows for representation; instead, queer themes and characters and storytelling have made their way into the mainstream in a manner that they hadn’t as little as 10 years ago. And along with that comes the ability for queer characters to start to invade genres that have long been seen as havens of heteronormativity. Game of Thrones adapted Martin’s amazing world, but more importantly they took Martin’s characters who were gay in rumor and subtext and placed their sexuality firmly in the text of the show. As such, we have a fantasy series with gay, bisexual, and asexual characters. Likewise, Orphan Black is a sci fi show which has featured gay (Felix), lesbian (Cosima), and even trans (Tony) characters in its young 2 season run. Even Penny Dreadful has found the time to work sexually ambiguous characters into its horror based story. As queer characters and storytelling grow to find itself more and more in the mainstream, it seems like typically heteronormative genres are starting to become more inclusive.

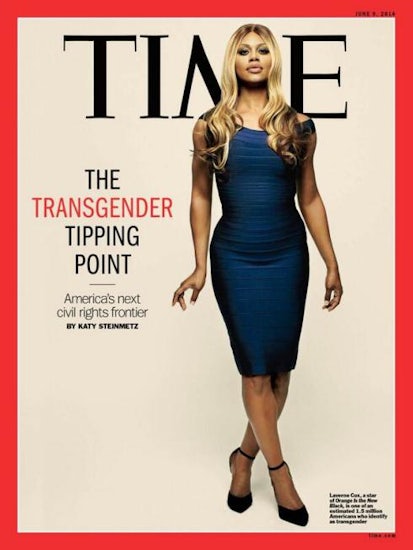

So we no longer have to look to exclusively queer shows for representation; instead, queer themes and characters and storytelling have made their way into the mainstream in a manner that they hadn’t as little as 10 years ago. And along with that comes the ability for queer characters to start to invade genres that have long been seen as havens of heteronormativity. Game of Thrones adapted Martin’s amazing world, but more importantly they took Martin’s characters who were gay in rumor and subtext and placed their sexuality firmly in the text of the show. As such, we have a fantasy series with gay, bisexual, and asexual characters. Likewise, Orphan Black is a sci fi show which has featured gay (Felix), lesbian (Cosima), and even trans (Tony) characters in its young 2 season run. Even Penny Dreadful has found the time to work sexually ambiguous characters into its horror based story. As queer characters and storytelling grow to find itself more and more in the mainstream, it seems like typically heteronormative genres are starting to become more inclusive. Speaking of Tony from Orphan Black, I think there’s also a case to be made that we’re seeing the start of a kind of trans revolution. Between Tony and Laverne Cox’s Sophia over on Orange is the New Black, I think it’s fair to say we haven’t had this much trans visibility on TV ever. While it certainly isn’t where I’d expect the struggle to end, I do think that the presence of these characters as well as the popularity of shows like RuPaul’s Drag Race, and the media focus people like Cox and Carmen Carrera have gained lately serves to start up a dialogue on gender issues within this country.

But the way that LGBT characters have progressed into more typically heterosexual shows isn’t the only progress queer storytelling has made. Even the more exclusively queer shows of the day have moved in a different direction than their predecessors. As much as I sang the praises of Queer as Folk last week, I think it’s possible that Looking could progress into an even better series if it withstands the test of time. The main difference that I see between the two is that Looking seems to be interested in its characters as more than just their sexual orientation. So where QAF might have been “more interested in making its point than it is in simply allowing its characters to be and its story to develop,” Looking is just interested in allowing its characters to be themselves and progress rationally in a lot of ways. The closest Looking gets to being an issue show (which I think is territory QAF often found itself in) is in the story of the interracial relationship between Patrick and Richie. But as a show with an established interracial couple, you’d think it would be a subject they’d tackle more often.

Likewise, I don’t think that Faking It is as interested in making broad points and delivering its core message nearly as much as The L Word was. Faking It is far more interested in allowing the story of Karma and Amy’s relationship to progress organically and allow the natural conclusions about the development of human sexuality to happen as they will. But another similarity between Faking It and Looking that set them apart from their predecessors is that both shows are half hour comedies instead of hour long dramas. In the case of Looking, the show isn’t bringing the comedy as forcefully as it could, but it’s still working harder to bring the laughs than QAF did. This shift out of issue based storytelling into a purer plot/character based storytelling is important and noticeable.

Likewise, I don’t think that Faking It is as interested in making broad points and delivering its core message nearly as much as The L Word was. Faking It is far more interested in allowing the story of Karma and Amy’s relationship to progress organically and allow the natural conclusions about the development of human sexuality to happen as they will. But another similarity between Faking It and Looking that set them apart from their predecessors is that both shows are half hour comedies instead of hour long dramas. In the case of Looking, the show isn’t bringing the comedy as forcefully as it could, but it’s still working harder to bring the laughs than QAF did. This shift out of issue based storytelling into a purer plot/character based storytelling is important and noticeable. I don’t know that these same sensibilities are being transferred over to other mediums. For the most part, film seems unchanged and anyone who might have been assuming that Brokeback Mountain’s release and relative success in 2005 would herald a new age of fearless mainstream queer cinema seems to have been wrong. But a lot of people (myself included) have been talking about how we’re in the midst of a TV renaissance, so it makes sense that the landscape is changing for the better. Better storytelling methods and better stories to be told have all led to a far improved atmosphere for queer characters and shows. Queer as Folk and The L Word did a great job of laying the foundation, but shows today have built upon that foundation to create something grander and more fabulous than even these shows could have imagined.